Edgar Harden's Resignation

Why Harden Resigned

In late March of 1965, President Edgar L. Harden had a dispute with Lincoln B. Frazier, a member of the university’s Board of Control. They had disagreed over Harden’s “Right to Try” policy, which gave any student the right to attempt to receive a college education regardless of their prior academic record. Both Harden and Frazier resigned from their positions as a result of this disagreement.

On April 1, 1965, the news of Harden’s resignation broke in Marquette. The newspapers reported that they had resigned in “an apparent conflict over university policy” and a “difference of philosophy over general administration”. Frazier said that he had never intended for Harden to resign over the issue. The next day, however, the newspaper headlines declared that Northern’s President would “stay on the job”.

What happened to change Harden’s mind?

Student Reaction to the Resignation

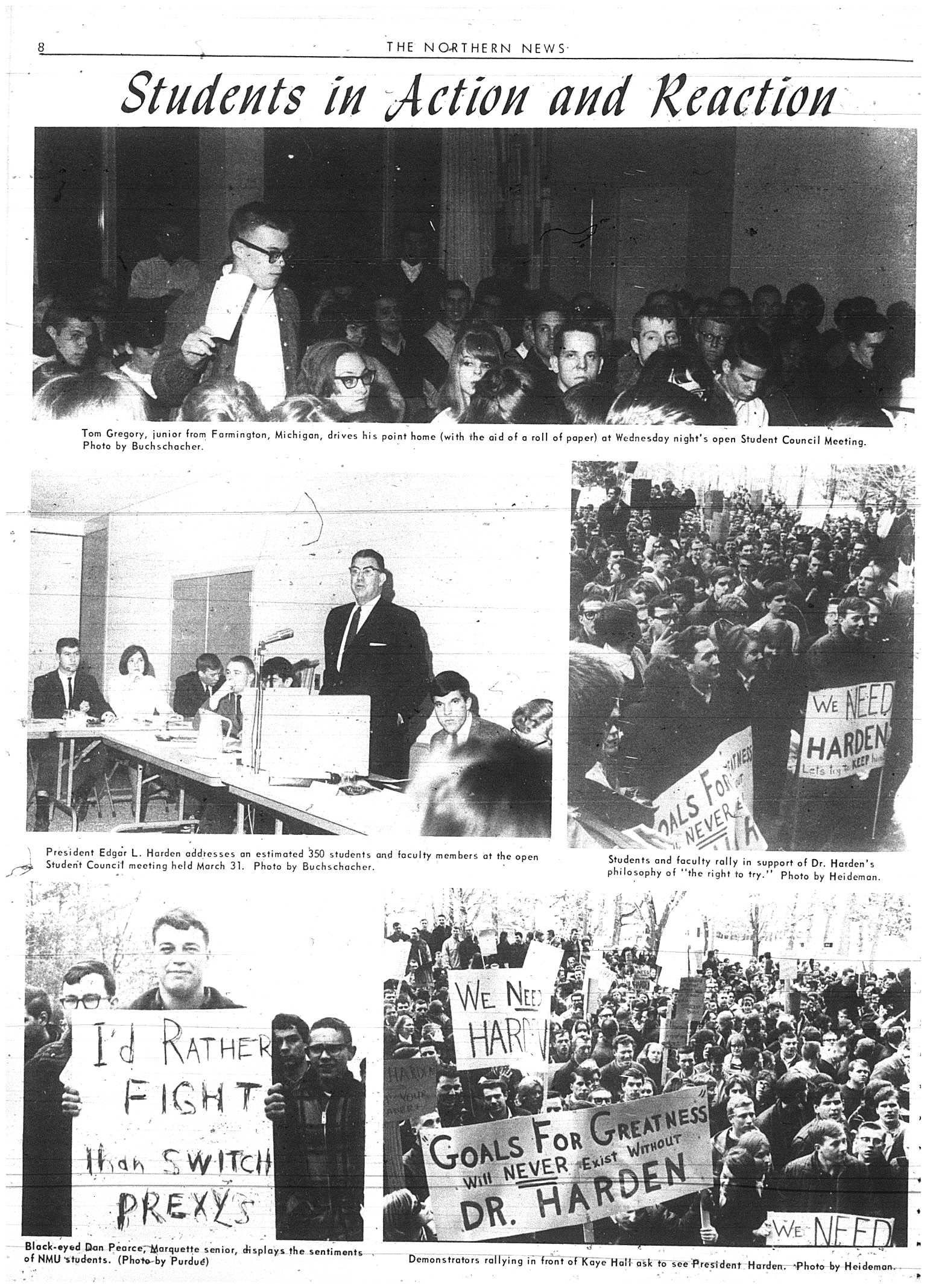

On March 31, 1965, the night before news of Harden’s resignation broke, President Harden had attended an open meeting of the student council in the hopes of defusing growing student unrest. Students were able to voice their opinions on such contentious issues as dress code, off-campus housing, regulations on what could be printed in the Northern News, and the general state of student-administration communications. Most of the administration was not thrilled about the potential changes. One administrator, Dr. Dickson, noted in the Northern News, “I am rather old-fashioned; I definitely believe that students should maintain the current dress policy for the evening meal at least. This climate, however, makes it difficult to insist on the skirts for girls rule.”

This drive for a liberalized university was not exclusive to Northern, and Northern students felt that they were part of a burgeoning national movement. One student wrote in the Northern News, “Northern isn’t alone! From Harvard in the East to Berkeley in the West students are crying for student unification and communication with their administrations.” At other universities around the state and country, students wanted the administration to give some rationale for the strict rules that they were required to follow. In an article for the Northern News, a student noted proudly that while some state schools used protests to get what they wanted, NMU students were mature enough to meet with the administration to create change. Elsewhere, a student noted that “Northern does not want another Berkeley.”

The next day, students heard on the radio at lunch that Harden had resigned in fury over a conflict with a Board member and decided to stage a protest that very afternoon in support of Harden’s university policies. As the Northern News would note a few days later, “support of President Harden and his philosophy of ‘the right to try’ was especially strong in light of the Student Council meeting the night before, where Dr. Harden had promised to work with students in reviewing current administrative policy.” Only an hour and a half later, a parade and rally had been organized in which two to three thousand students and some faculty members marched to Kaye Hall. According to the Mining Journal, it was the “biggest demonstration ever witnessed in Marquette” up to that point. Other students sent telegrams to the governor in support of Harden and asked him not to accept Harden’s resignation. Technically, only the Board of Control could accept or deny his resignation. However, the Board was appointed by the governor and, as shall be seen, the governor had a large amount of clout in the matter of whether Harden was allowed to resign or not.

The Mining Journal described the event:

“Students carrying hastily made signs marched across the campus chanting ‘We want Harden’. They gathered in front of Kaye Hall, where Dr. Harden’s office [was] located, for a rally. Dr. Harden, who was attending a meeting at the time, did not address the students. Signs read ‘Goals for Greatness Cannot Be Achieved without President Harden’, ‘We Need President Harden’, ‘Steady Eddie Is Our Man’, ‘Down with Frazier’, and ‘We’d Rather Fight Than Switch Prexies.’ ‘A precedent was set in that we were not demonstrating against something but for something’, said Settle and Graf [two student leaders of the protest]. ‘The students were demonstrating their total support of Dr. Harden and his philosophy of education, which is the right of students to try. This was probably one of the largest demonstrations that has taken place on any college campus. But everywhere else, the student body has made demands on the administration in their demonstrations. We weren’t doing that. This was a constructive demonstration rather than a destructive one….This was our answer to Dr. Harden, who gave us the right to try’“.

Re-instatement

Most of the students believed that Harden’s re-instatement was due to their efforts. However, while Harden said that the protest was “the most heart-warming experience in [his] life”, the protest was not the primary factor that convinced him to stay at Northern. Governor George Romney and Edwin O. George, a Board of Control member, flew to Marquette and spoke to Harden, urging him to stay at Northern and telling him that they supported his educational philosophies. Harden agreed to stay and Frazier was fired.

Many in the Northern community felt that Harden’s resignation was mere histrionics to show that he had leverage against the Board of Control and the governor—if they thought he was improving Northern and wanted him to stay, they had to acquiesce to his plans including the “right to try.” Harden claimed in an interview years later that his resignation was genuine and he had intended to go through with it.

The End of the School Year—Students Have Hope that Apathy Has Ended

As the 1964-1965 school year ended, many students were hopeful that NMU was entering a new era in which students would be more involved in campus life. The council meeting and the protest prompted the creation of a new student constitution which would form a larger and more representative student government, the format of which was based on the United States branches of government. One interviewee who went to Northern during these years (Pat Stapleton), stated that the previous student council had largely been controlled by the fraternities and was virtually ineffective when it came to larger university policy. As students sought to have more say in the way in which the university was run, they realized that they needed a revised system of governance with more actual power.

Many students optimistically believed that the events of the previous months marked the beginning of Northern coming into its own as a real university. They hoped that student apathy had ceased and that the student body was now willing to work for change. They also believed that Northern was above other universities, who had primarily protested against policies with which they disagreed. Northern students had protested for their administrator while addressing their problems through dialogue rather than demonstration.